Step into the heart of New York, London, or Chennai and try to count the cameras. Within seconds, you’ll lose track because they’re as common as street signs.

In 2024, an estimated 1 billion surveillance cameras were in use worldwide, with China alone accounting for more than 600 million. In cities like London and New York, there are roughly 20–30 cameras for every 1,000 people.

Security cameras are everywhere, but the path that brought them here and the direction they’re headed is a story of innovation, ambition, and a bit of mystery.

From ancient watchtowers to today’s advanced security operations centers, the history of video surveillance is a story of humanity’s need to observe, understand, and act.

The all-seeing eye

Long before glass lenses and image sensors, the concept of surveillance was already shaping how people built, ruled, and defended their worlds.

In ancient civilizations, the “all-seeing eye” wasn’t a metaphor, it was a design principle. Elevated watchtowers dotted city walls, giving guards a sweeping view of the land. Temple entrances were flanked by statues with unblinking eyes, symbols meant to remind visitors (and potential troublemakers) that their actions were being observed.

From the fortified cities of Mesopotamia to the ramparts of medieval castles, watchpoints were placed with surgical precision. Sightlines were maximized. Blind spots were minimized. A single watchman could see hundreds of feet in every direction, spotting the dust of an approaching army or the flicker of a torch in the night.

It was early security intelligence: detect threats early, interpret what they mean, and act before danger arrives. The tools were basic, but the intent was modern, continuous monitoring for early intervention.

These ancient systems also had their first and most enduring limitation: human attention. Fatigue, distraction, and misjudgment meant even the tallest tower or widest field of view could fail when vigilance slipped.

The lesson still applies today. Technology may extend our vision, but someone or something must always interpret what’s being seen.

From towers to innovation

For thousands of years, surveillance relied on elevation, eyesight, and endurance. That changed in the 20th century, when the job of “watching” began shifting from humans to machines.

But even before electricity, societies experimented with ways to extend human vision and improve monitoring. Notable innovations included:

- Early communication systems: Ancient Greek beacon fires and 18th-century French semaphore towers enabled rapid, long-distance information transfer using visual signals.

- Optical advancements: The telescope, invented in the early 1600s, enhanced surveillance by allowing watchmen to monitor distant ships or enemy movements with greater clarity.

- Observation posts: By the 19th century, military forts and coastal defenses used elevated rooms with binoculars, maps, and basic rangefinders, making surveillance more systematic and data-driven.

These innovations didn’t capture or store images. Still, they transformed observation from a purely human skill into a structured system, laying the groundwork for the leap to mechanical and electronic surveillance in the 20th century.

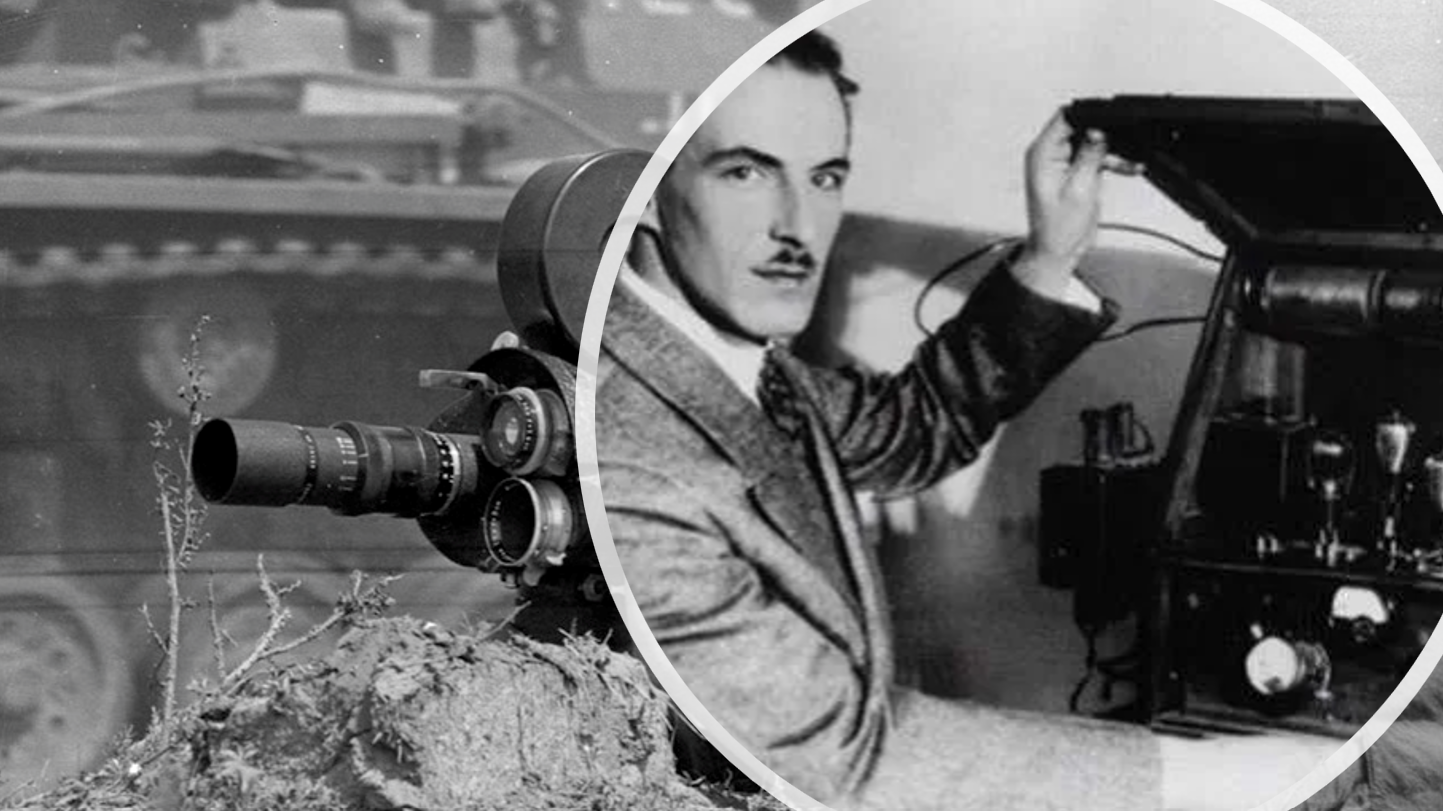

The birth of mechanical surveillance

By the early 20th century, the watchman’s post was no longer the pinnacle of observation. Industrialization, expanding cities, and global conflict created both the means and the urgency for a new kind of surveillance.

In 1927, Russian inventor Leon Theremin developed what many consider the first closed-circuit television system. Using a camera paired with a shortwave transmitter allowed Kremlin security to monitor visitors in real time from a separate location.

Russian inventor Leon Theremin

Fifteen years later, another breakthrough came during World War II. In 1942, Germany’s military deployed a CCTV system to observe V-2 rocket launches from a safe distance. Operators could watch live images over a direct video feed, avoiding the dangers of being near the launch site.

For the first time, the human eye was replaced by an electronic one.

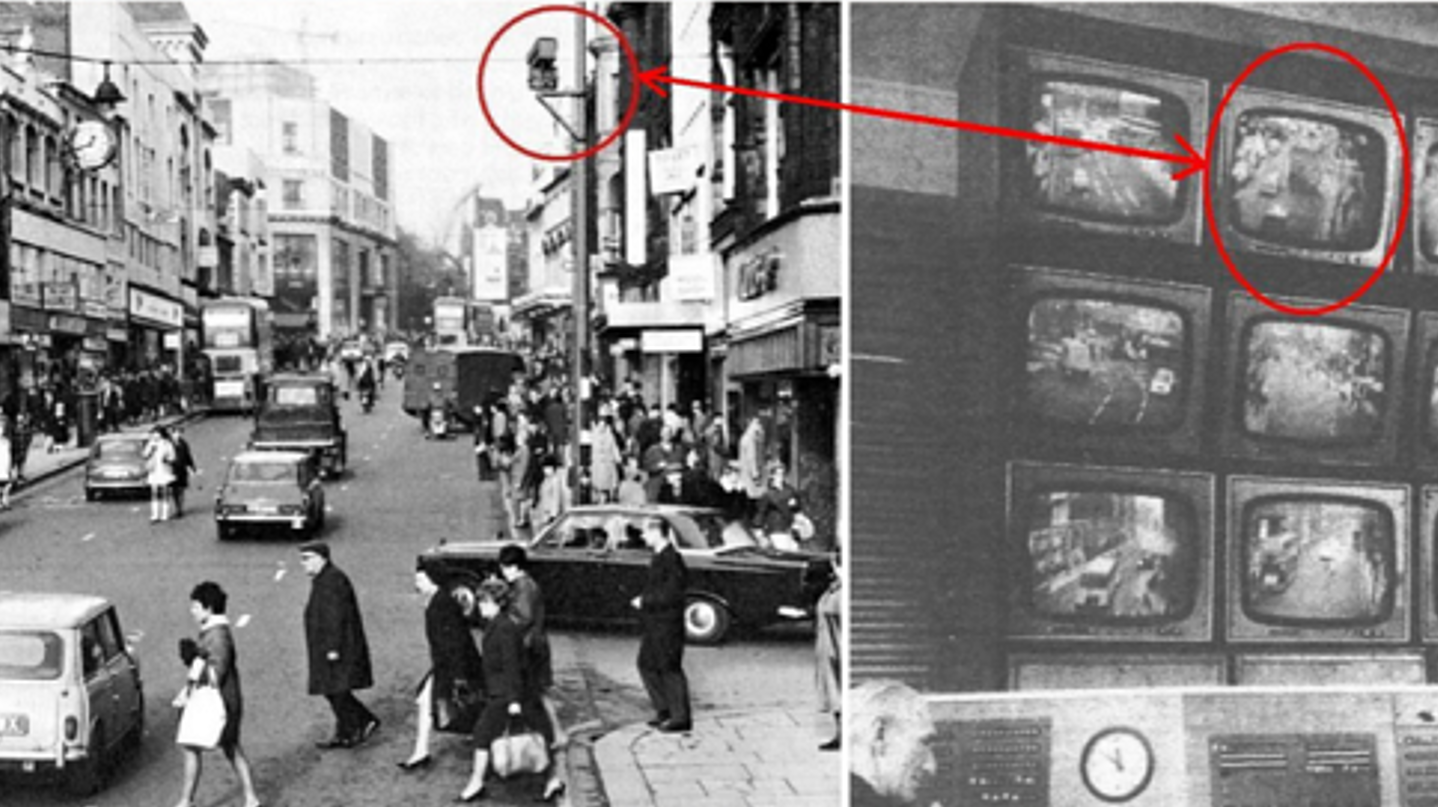

Civilian surveillance takes root

By the 1960s, civilian uses began to emerge. The UK tested cameras for traffic monitoring in busy intersections. Banks in the U.S. installed them as robbery deterrents.

The feeds were grainy, the equipment bulky, and recording was still rare, but the concept had taken hold: you didn’t need to be there to see what was happening.

For security professionals of the time, it was a double-edged sword:

- Coverage expanded-cameras could now watch areas without guards.

- Operational demands grew-skilled operators were needed to monitor feeds in real time.

- Maintenance became critical -bulky equipment required constant upkeep to stay operational.

- No recording meant no rewind -once a moment passed, it was gone forever.

The foundation was set, the next leap would be capturing and preserving what the cameras saw, turning fleeting images into lasting evidence.

Tape, time, and the birth of the archive

Early CCTV may have expanded the reach of surveillance, but it came with a fatal flaw. Once the moment passed, it was gone.

That changed in the 1970s and 80s, when videocassette recorders (VCRs) made it possible to store hours of footage on magnetic tape. For the first time, security teams could rewind, review, and preserve visual evidence.

Still, the system was far from perfect. Tapes degraded over time. Storage rooms filled with boxes labeled “Do Not Erase” but rarely, if ever, reviewed. Critical footage was sometimes lost because a tape was reused too soon.

And then there was the human factor: someone still had to know where to look, when to rewind, and what to look for.

The problem wasn’t solved, it was simply preserved. The next leap would be digital, searchable, and far faster.

Cameras meet the network

By the late 1990s, VCRs were phased out as digital video recorders (DVRs) emerged, storing weeks of footage reliably without the degradation of magnetic tapes.

For security teams, it was like swapping a typewriter for a laptop, searching footage became faster, image quality improved, and the days of manually swapping tapes were numbered.

Then came the real game-changer: IP cameras. No longer bound by coaxial cable runs or local recorders, these cameras transmitted video over networks. With the right setup, a security director could view a live feed from the other side of the building or the other side of the world.

The possibilities exploded:

- Scalability – Adding cameras no longer meant rewiring an entire facility.

- Remote access – Incidents could be monitored and managed from anywhere.

- Integration – Video could be tied to alarms, access control events, and building systems.

But new capability brought new challenges. Network outages could kill visibility. Bandwidth demands grew.

The next leap wasn’t about more storage or higher resolution. It was about teaching the system to decide what mattered most before a human ever pressed “play.”

The analytics era

Early video analytics started small, simple motion detection, object tracking, and alerts when something entered a restricted area. It was useful, but it still relied on humans to interpret what they were seeing and decide whether to act.

Then processing power caught up with ambition. Innovators like ObjectVideo pioneered commercial analytics software in the early 2000s, laying the groundwork for intelligent detection.

Manufacturers such as Axis Communications and Bosch Security Systems began embedding analytics directly into cameras, eliminating the need for separate servers. Algorithms could now recognize faces, read license plates, track vehicle movement, and even flag unusual behavior patterns in crowds.

For security teams, this was the shift from footage to foresight:

- Detecting loitering before a break-in.

- Flagging a vehicle that circles a property too many times.

- Spotting abandoned bags in public spaces.

Analytics had made surveillance faster, smarter, and more predictive. The final hurdle was the same one it had always been: keeping the system healthy, connected, and aligned with real-world security needs.

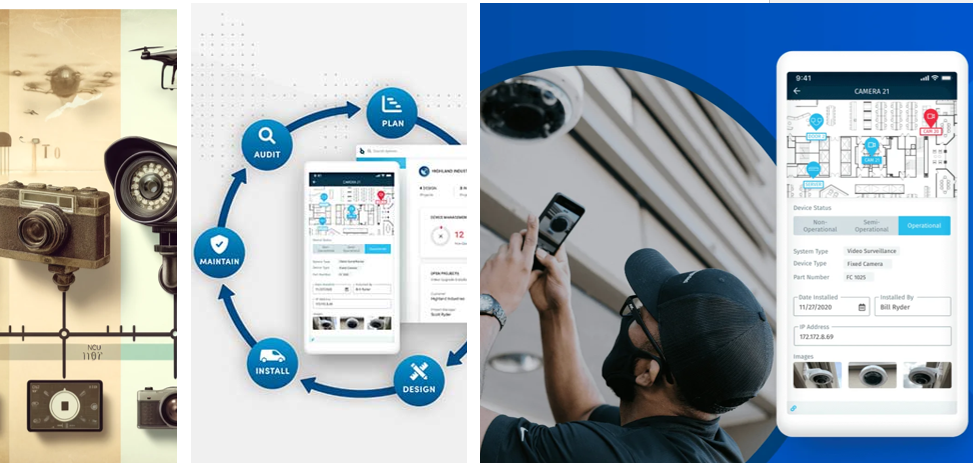

The lifecycle of an all-seeing system

Modern surveillance networks are impressive, with thousands of cameras, intelligent analytics, and instant alerts, but no system is truly “set it and forget it.”

Cameras get knocked out of position. Card readers are relocated. Warranties lapse. Workspaces are reconfigured. Each small issue chips away at the system’s reliability until, one day, the “all-seeing eye” isn’t seeing nearly as much as everyone assumes.

For a security program to stay effective, surveillance technology needs the same disciplined care as any other critical infrastructure. That means:

- Accurate inventory: Know exactly what’s in your system and where it lives.

- Proactive health checks: Catch issues before they become blind spots

- Change tracking: Record every update, repair, and replacement.

- Planned refreshes: Replace aging gear before it fails.

This is lifecycle management, treating your surveillance ecosystem as a living system, not a one-and-done project. It’s the difference between assuming you have coverage and knowing you do.

Because in the end, the true measure of an all-seeing eye isn’t how many feeds it collects, it’s how ready it is to act when you need it most.

Want to get more from your physical security systems? Download SiteOwl’s Security Infrastructure Guide to see how cloud technology can extend lifecycle and strengthen your security posture.

David Santiago

David is a Physical Security Professional and SiteOwl contributor. From his service in the U.S. Marine Corps to leading campus-wide security initiatives, David brings deep operational insight. When not writing or consulting, he enjoys tai chi, playing basketball, and chasing the perfect beach sunset with his family.