Walk the floor at ISC West or GSX, and the future of access control is on full display. Biometric scanners light up. Phones tap open doors. Systems recognize you before you speak.

But the core question hasn’t changed: Who gets in, and who doesn’t?

Access control has come a long way since wooden locks in ancient tombs. Today, it’s not about if you can secure a space, but how you do it and how well it holds up.

Here’s how we got here and what physical security professionals can learn from the systems, strategies, and missteps of the past.

Ancient access control

Access control wasn’t born in a server room; it started with wood, pins, and a problem.

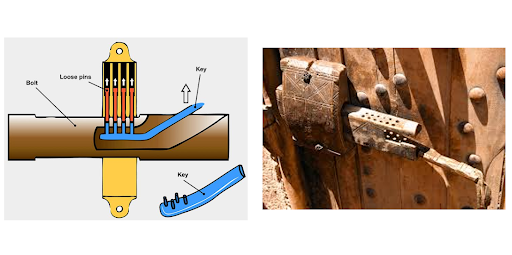

The first known lock, an Egyptian pin tumbler, dates back to around 2000 BCE. Made of wood and discovered in the ruins of Khorsabad, it worked by lifting a set of pins when the correct key was inserted, allowing the bolt to slide free.

The invention of the lock in ancient Egypt was not a whimsical creation but a necessary innovation driven by the very structure of its society. For the Egyptians, the lock was a crucial tool to protect not just their material goods, but their economy, their social order.

So, Egyptians didn’t just build locks. They built systems. Locks secure doors. Keys were handed to trusted stewards. Access was intentional, managed, and monitored—at least as much as possible.

If you want to see just how seriously Egyptians took security, look at the pyramids. They designed elaborate traps, massive stone doors, hidden chambers, all to keep robbers out. And yet, almost every tomb was breached.

No system is perfect. But every system tells a story about what people were trying to protect and what they were trying to prevent.

Lessons from ancient Egypt for modern security

Thousands of years later, the fundamentals haven’t changed. The tools are smarter, but the challenges remain familiar. Here’s what still holds true:

- Attackers adapt. Tomb robbers found a way in. So do modern intruders. Systems need to adapt faster than threats.

- Barriers aren’t enough. Egypt went all-in on physical defense. Today, true access control combines hardware, software, and human factors.

- Blind spots cost you. Once a tomb was sealed, there was no visibility. Today’s systems offer oversight but only if used well.

- People are still the weak point. Then it was a loose-tongued builder. Now it’s a shared credential or a door left ajar.

Where Egypt brought locks into the world, Rome refined them. With stronger materials and smarter designs, Roman engineers took access control to the next level.

Roman metal, mechanisms, and control at scale

The Romans didn’t invent the lock, but they made it better. By introducing iron and bronze, they created locks and keys that were smaller, tougher, and more precise. They also developed warded locks, adding internal barriers to keep the wrong key from turning.

It was a leap in both security and sophistication. But Roman access control didn’t stop at doors.

It scaled into homes, into streets, into the design of cities. Walls, gates, checkpoints, and human gatekeepers turned movement itself into something managed, observed, and deliberately restricted. Security was infrastructure. And infrastructure was power.

Romance access control & modern physical security

Many of Rome’s access control methods may feel ancient, but the ideas behind them still show up in modern physical security:

| Roman access control method | Modern equivalent |

| The warded lock & metal key

A physical lock using internal obstructions (wards) requiring a key with a specific pattern. |

Mechanical keys & locks The direct descendant. Modern pin-tumbler and lever locks still rely on a uniquely shaped key interacting with internal mechanisms to grant access. |

| Ornate keys as status symbols

Elaborate, portable keys, sometimes worn as rings, signifying the owner’s authority and wealth. |

Access credentials

Executive keycards, restricted-access badges, and tiered credentials serve as physical indicators of role-based access within enterprise environments. |

| The Ianitor (Doorkeeper/Porter) A dedicated person positioned at the entrance to identify and physically block or grant entry to visitors. |

Visitor management

Security guards or systems to verify IDs, manage visitor logs, and issue temporary credentials. |

From empire to control at scale

In Rome, managing access meant more than protection. It was how you enforced laws, kept order, and controlled the movement of people through streets, homes, and entire regions.

Today, enterprise security teams face the same challenge, just a global scale. Securing offices, campuses, industrial sites, and data centers is no longer about just locking doors. It’s about visibility, accountability, and control across an entire ecosystem.

Access control now lives at the intersection of policy, technology, and user experience. And it’s essential.

- Over 70% of organizations with access control report fewer than five major incidents per year.

- The access control market is projected to grow from $10.4 billion in 2024 to $15.2 billion by 2029.

The Romans built the foundation. But even they understood that every system has limits. When those limits are reached, new defenses emerge.

Centuries after Rome fell, one of those ideas came from 13th-century engineer Isma’il al-Jazari, who sketched designs for the world’s first known combination lock.

It marked a shift from access based on what you possess to access based on what you know, a concept that still underpins the passwords, PINs, and access codes we use today!

Medieval layered defense

In medieval Europe, castles were the pinnacle of security technology for their age. The core principle behind castle security was “defense in depth.”

An attacker wasn’t faced with a single barrier, but a succession of obstacles, each one harder than the last. The goal was to exhaust, thin out, and demoralize an invading force long before they ever reached the castle’s heart, the keep. Access control was the first and most critical part of this strategy.

The most iconic feature, the moat, provided a formidable water or dry ditch obstacle. Whether filled with water or dry, it forced a single point of entry through the drawbridge. Winches and counterweights allowed defenders to raise it in seconds, instantly cutting off access.

Next came the portcullis, a heavy iron-and-wood grille that dropped vertically to block the main gate. It wasn’t just symbolic. It was brutal, effective, and fast.

These weren’t just architectural flourishes. They were access control mechanisms built to delay, detect, and deny.

A more modern echo of this strategy can still be found in the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest masonry fort in the continental U.S. Its dry moat and layered defenses reflect the same logic that shaped castles centuries earlier: security as a series of physical hurdles.

But even the most fortified strongholds had limits. They relied on human vigilance, close-range conflict, and relatively slow threats. As warfare evolved and technology advancedphysical barriers alone stopped being enough.

That shift began with the Industrial Revolution.

Industrial precision and scale

The Industrial Revolution reshaped everything, including access control.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, hand-forged gates and locks gave way to mass-produced hardware. Standardized parts, precision machining, and factory-scale manufacturing made locks more consistent, more affordable, and scalable across cities, industries, and institutions.

In 1778, English locksmith Robert Barron patented the double-acting tumbler lock, a leap forward in complexity. Unlike earlier designs, Barron’s mechanism required two tumblers to align perfectly for the bolt to release. It raised the bar for security and quickly became the new standard.

But even the best technology meets its match.

At the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, American locksmith Alfred Charles Hobbs famously picked the “unpickable” Bramah lock in front of a live audience in under 25 minutes. It shook public confidence and kickstarted a race for better, smarter designs.

That cycle of trust, breach, and redesign still defines access control today.

Familiar failures, modern tools

We’ve seen similar moments in recent decades, incidents where trusted systems were bypassed in ways that seemed unthinkable:

- In 2022, attackers exploited misconfigured permissions in a popular cloud-based access control system, unlocking doors at multiple facilities remotely.

- In 2013, cloning devices hit the market, exposing widespread vulnerabilities in unencrypted RFID keycards still used in offices and hotels.

Even today, many organizations lose track of what’s installed, where it is, or if it’s still functioning. As systems age and staff change, doors get added, panels go offline, and documentation disappears.

Over time, missing records, outdated hardware, and forgotten devices quietly erode the integrity of a security system, creating gaps that are hard to spot and even harder to fix.

And as the past keeps showing us what you can’t see is often what takes you down next.

Electrification and the era of convenience

The early 20th century marked a shift from mechanical locks to electrically powered systems. No more tumblers, no more heavy iron keys. Now, security ran on circuits.

In the 1930s, hotels led the charge with electric key systems. Insert the key, complete the circuit, unlock the door. It was faster, more consistent, and easier to scale across properties.

By the 1960s, magnetic stripe cards entered the scene. Originally designed for ATM transactions, they were quickly adopted for physical access. Swiping a card felt modern, ideal for banks, office buildings, and secure facilities.

In the 1970s, a disgruntled employee in a New York office building duplicated a magnetic access card and used it to steal sensitive documents.

The message was clear: if credentials are easy to copy, they’re easy to exploit.

The 1980s brought a new wave of tech: proximity cards using RFID. No contact required just hold a badge near the reader and go. Hospitals, universities, and corporate campuses embraced the convenience.

But again, convenience had a cost. Card skimming, cloning, and weak encryption introduced new threats. What started as a smart upgrade became a quiet liability when left unmanaged.

What still applies today

Much of today’s access infrastructure still runs on tech from this era. Magnetic stripe and RFID systems remain widespread, even as their weaknesses are well-documented.

- Cloning devices are cheap and easy to find.

- Outdated readers often lack support for encryption or multi-factor authentication.

- Lost or stolen credentials frequently go untracked unless tied to a centralized system.

- Legacy hardware and disconnected records create visibility gaps often without anyone realizing it.

As buildings get smarter, access control is expected to keep up. But too often, it’s the weakest link in the chain.

Digital age of access control

By the late 20th century, access control began to move from what you have a key, a card to who you are. Biometrics like fingerprints, iris scans, and facial recognition moved out of science fiction and into security protocols.

A major turning point came in 2001, when San Francisco International Airport deployed fingerprint scanners for employee access. Within a year, unauthorized entry incidents dropped by 30%. It was a bold proof of concept: identity-based access could reduce risk and boost accountability.

But early systems weren’t perfect.

False rejections were common. Environmental factors dirty fingers, bad lighting, and worn sensors, created user friction. Security teams quickly learned that biometric precision came with a cost: complexity, user frustration, and the need for reliable backup systems.

From novelty to infrastructure

Fast forward to today: biometric access is everywhere.

Phones unlock with a glance. High-security facilities rely on palm vein and iris recognition. Some corporate campuses have phased out badges entirely, opting for multi-modal biometric authentication.

The promise is clear: faster entry, stronger security, and no more worrying about lost cards. But in practice, the shift to identity-based access has introduced a new layer of complexity and a familiar set of tradeoffs.

The core challenge? Scaling biometrics without compromising speed, privacy, or trust.

- Identity matters, but context is king. A fingerprint isn’t enough without time, location, and role in the equation.

- No method stands alone. Biometrics work best when paired with PINs, cards, or mobile credentials.

- Lifecycle still rules. Devices degrade. Databases drift. Systems need regular oversight to stay secure.

- User experience drives compliance. If access is slow or unreliable, users will find workarounds and those are rarely secure.

Biometrics have come a long way. But they’ve also raised expectations and the stakes. For physical security leaders, success isn’t just about adopting new tech. It’s about deploying it with context, maintaining it over time, and making sure it actually works for the people using it.

Value of lifecycle management in access control

From ancient tombs to digital credentials, access control has advanced, but one truth hasn’t changed: systems fail when they’re ignored.

For modern security teams, lifecycle management is no longer a back-office task. It’s the backbone of a secure, scalable strategy. That means treating access control not as a one-time deployment, but as a living system that needs visibility, structure, and accountability.

As threats grow more sophisticated and environments more dynamic, success won’t just come from adopting new technology. It will come from mastering the full lifecycle design, deployment, operation, and beyond.

Access control has always been about control. Now it’s about clarity too.

Take charge of your physical security infrastructure. Monitor, track, and manage with confidence.

Request a demo today and see the future of access control lifecycle management.

David Santiago

David is a Physical Security Professional and SiteOwl contributor. From his service in the U.S. Marine Corps to leading campus-wide security initiatives, David brings deep operational insight. When not writing or consulting, he enjoys tai chi, playing basketball, and chasing the perfect beach sunset with his family.